Two small slits

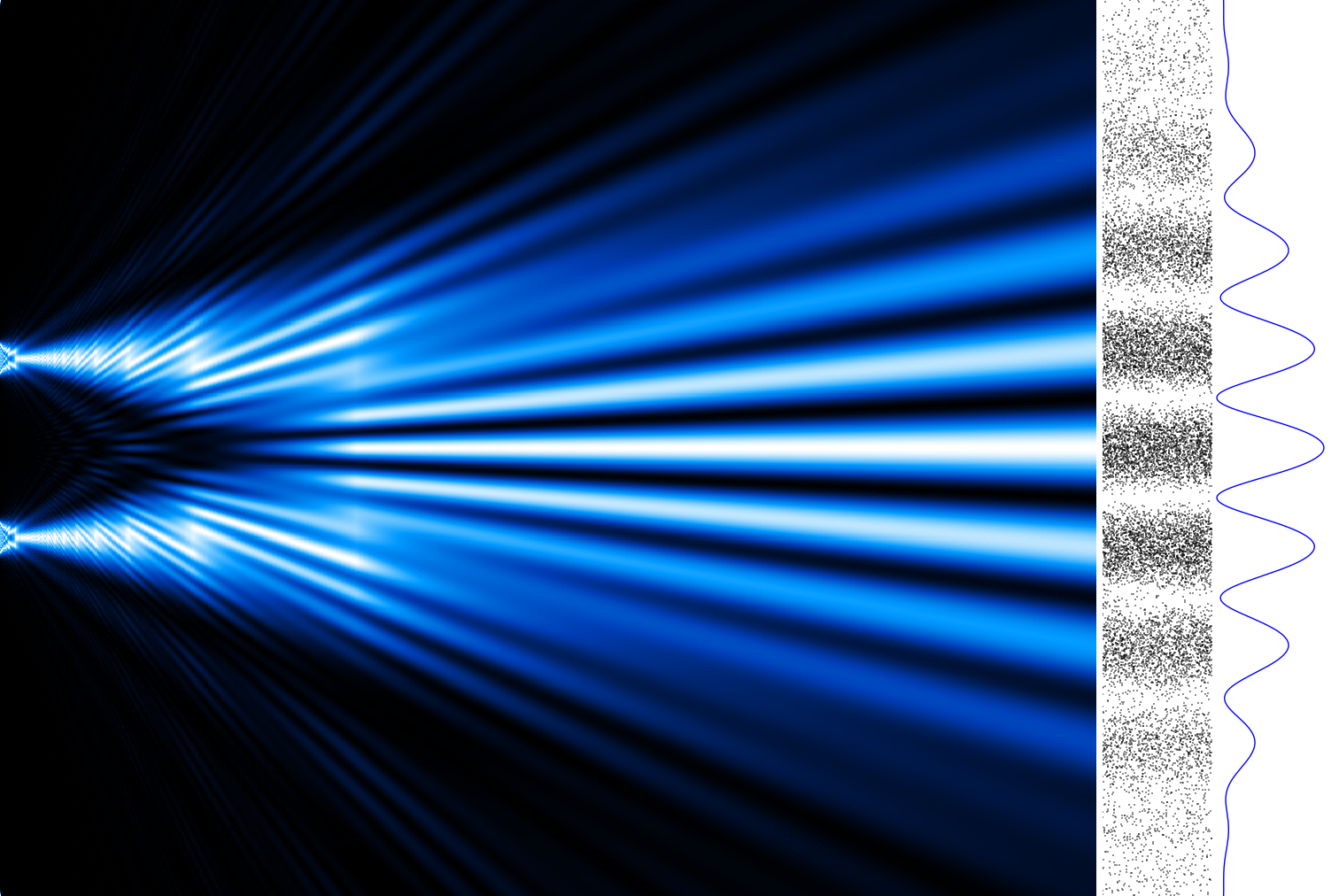

About ninety years ago, let’s say about a hundred years ago, an experiment changed the concept of reality. Einstein himself did not dare to believe it. The experiment was based on Thomas Young’s 1801 experiment, which showed that light was a wave. It is pretty simple. Place a light source in front of an obstacle with two equal openings. On the other side, on another wall, you will see a pattern that looks like what is produced by a wave on water. When the light waves cross each other, they form patterns, canceling out or amplify each other in the same way as in water, into which two stones are thrown simultaneously.

At the beginning of the 20th century, it was realized that it was not so simple. If we reduce the light source to a single photon, the photon being the elementary particle of light, the same wave pattern appears on the other side, which is contradictory because a single photon should have passed through only one of the two slits... We deduced that light had a dual nature, both a wave and a particle. This is already quite disturbing. Let us complicate the experiment by obliterating one of the two slits. The photon passes through the open slit but no longer produces interference. The photon has become a particle. Roughly speaking, and if I understand it correctly, light is a wave when we test its wave quality but becomes a particle if we try to detect... a particle. It is the type of experiment that dictates the result. The observations’ conditions destroy an aspect of reality to respect our desire for the result. In short, reality without us does not exist.

A hundred years ago, physicists began to perceive a universe that only appears if we measure it in a certain way. We can certainly think that this defect comes from our capacity to observe. It is due to the poverty of our measuring instruments.

However, the mathematics behind these discoveries, of rather cold logic, confirms that it is indeed here that the whole operates. Man, said the ancients, is the measure of the universe. There is no false pride behind this statement. Being part of this world, our species, gifted with the capacity of reason (perhaps not all the time with success), discovers what is because it is part of this world. There is no separation between us and the universe. Without us, the universe, at least our universe, is not observed. It does not exist.

The majority of physicists are behind the Copenhagen interpretation, namely that this discovery does not matter. Seven axioms have been put forward, which can contradict each other, but which coexist.

One can very well continue to measure the universe and obtain convincing results. The proof, the quantum computers, the computer science, and the Internet. We live with the paradoxes inherent to our discoveries, and we do not go looking for the *why* of things. Knowing why this is so is not the object of science.

After all, how could we live if, from one day to the next, human beings lost themselves in philosophical considerations rooted in the archaic intuitions of Hindu thought or of the Australian witchdoctor?

There are other physicists, few in number, but still, big ones, who have never been satisfied with this way of thinking. For them, asking the question of "how can it be?" or "why?" should take its place in scientific questioning. They also manage, with other hypotheses, to describe reality by adding the dimension of consciousness, whether it is individual or universal (here, we speak of a universe that thinks itself).

When we have reached the point where we can transfer information from one quantum to another without them touching or being close to each other, how can we be satisfied with an interpretation that some people will associate with voluntary blindness? Are we afraid?

It is now one hundred years since reality is no longer that of Newton, since some scientists tell us that our conception of reality is outdated, that our convictions are in fact a virus that feeds tirelessly on the poverty of our senses.

It is true that the makers of good news and commercial mysticism or ill-behaved have thrown themselves on these discoveries without proving anything. One can understand those who prefer the Copenhagen axioms because no place is made in them for the charlatans who flood the bookshops. It is too easy to color the unknown with the curtains of our fears. We exist, we sit on chairs, we feed ourselves with the matter, we touch ourselves because we are things. But this border would be thin, even imaginary. How long, how many centuries, how many millennia will the human species need to overcome a conception of reality that is only two hundred years old? We are not eternal in the form that we know. It is quite possible that, if we survive in a way to our body, we would not be, in any case, ourselves, would be only information returning to the fold of the universal memory.

Does this really make sense?

Is it true that ancient man spoke to trees before the invention of reality and that it would only take a little passion and openness to be able to do so again? Is it true that the universe is too coherent to be the result of chance? That it is the same everywhere? Isn’t there a mystery that should make us humble and, above all make us stop the massacre of our lives and our planet?

Let’s forget the churches and their certainties, but let’s keep our eyes open to dreams and imagination?