Mors tua, vita mea

This morning, I chopped vegetables: an onion, some carrots, two small potatoes, a rutabaga, and two leek stalks. I heated a pot and added a little oil. I placed chicken drumsticks in it, browned them, and then added the first batch of vegetables, setting aside the potatoes and carrots.

I flooded the mixture with water and seasoned it with thyme, freeze-dried garlic, celery seeds, ginger paste, and pepper. After an hour of slow cooking, I added the carrots and potatoes.

Throughout the cooking process, I checked the state of the soup, adjusting here and there without interfering too much. Time would do its work.

When it was time to serve, as I try to do as often as possible, I offered thanks—to some unknown Reality—for the meal I had the luxury and fortune to prepare. The passage from Federico Faggin’s somewhat strange yet thought-provoking book quoted above came back to mind.

Mors tua, vita mea. I need your death to sustain my life. I prepare what my body compels me to consume from what fails in my hands. It doesn’t matter if one is carnivorous or vegetarian, a single-celled organism or a mammoth; life dictates its necessities. One must eat, kill, cut, chop, pulverize, and soften flesh to exist. This is undeniably a form of violence.

That is not the theme of Faggin’s book, though. Its subtitle is Consciousness, Life, Computers, and Human Nature. As the microprocessor inventor, he first garnered attention with his autobiography, Silicon. I’m not sure I want to follow the author where he leads us—to the thesis of a consciousness called One. I haven’t finished the book yet, as the first part offers an intriguing reflection on life and intelligence—true intelligence, not the supposed magic of AI—but the second part seems to drift into a quantum theology articulated by a kind-hearted man who, at some point, had his Damascus moment while futilely attempting to recreate consciousness in machines.

Still, it’s a book worth reading to explore the distinctions between Life and Object, Consciousness and Machine. I’ll eventually finish it, but another book about the brain occupies all my neurons. I’ll likely discuss it another time.

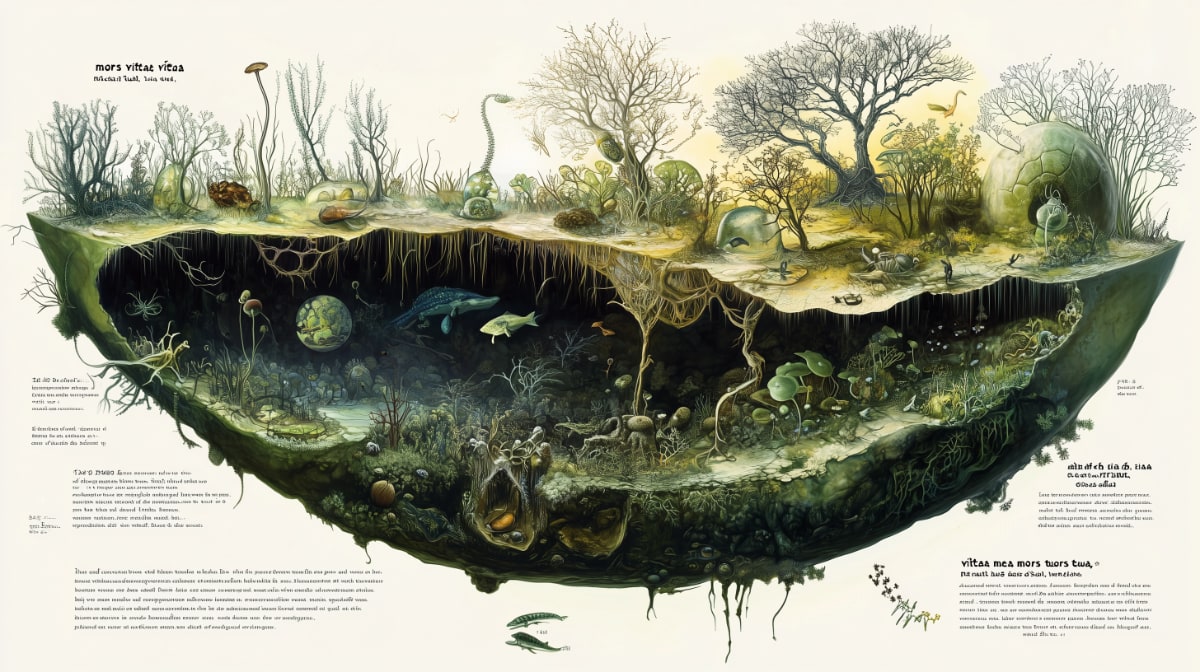

Let’s return to life and death. Faggin is no longer the only one pointing this out: reductionist science has created wonders, but both science and its discoveries have their limits. We won’t achieve our goals if we stubbornly see only trees while ignoring the organic forest of the universe.

I asked Perplexity to describe the expression inspiring this text.

The secret to the “sauce”—almost a truism—is balance. If killing is necessary to live, prudence and frugality are imperative. We are constantly, and rightfully, reminded that we are consuming the planet and that the resulting imbalance will lead to our demise.

Perhaps the end of our existence, on Earth or in the universe, is the necessary death for life elsewhere to flourish. It doesn’t matter. Our ignorance compels us to make do with what we hold in our hands.

The Darwinian dance suggests it isn’t necessarily the strongest who prevails but often the cleverest—the one who thinks and broadens their perspective.

I have no remorse for immersing chicken drumsticks in my soup. However, I’d like to believe that the three birds who once walked with these thighs were treated well. I don’t think they were happy in the sense we attribute to that emotion. Happiness for them was to live. And it will always be our responsibility, as the self-proclaimed supreme beings of this planet, to give them the chance to be what they are.

As for the vegetables, plants, and seasonings, they existed long before us, knowing in some way how to live and die. They have grown on so many soils since the Earth cooled…

So, thank you, life, death, and faith, for being brave links in the chain of Existence.

The soup was very good.