On God's periphery

Preamble

After reading All Things are Full of Gods by David Bentley Hart, I began a “conversation” with ChatGPT to compare my impressions with what the AI might summarize. What follows is the result: a blend of generated text, answers to my clarification requests, and more personal commentary born from the tangled workings of my free and feverish neurons.

The author is a Christian philosopher and theologian. His erudition seems boundless to me, and his style can be challenging to follow at times. He makes frequent use of neologisms, and I suspect he enjoys a labyrinthine and scholarly prose, sometimes at the expense of readability.

I had previously read his “The Experience of God,” and “All Things Are Full of Gods” is, in many ways, a logical continuation—ten years later—of the theses presented in that first book. Hart targets one of the central tenets of modernity: materialism. Against this vision of the world as purely mechanical, cold, and devoid of meaning, Hart defends an ancient thesis: the world is full of presence, of consciousness, of significance—in a word, full of gods.

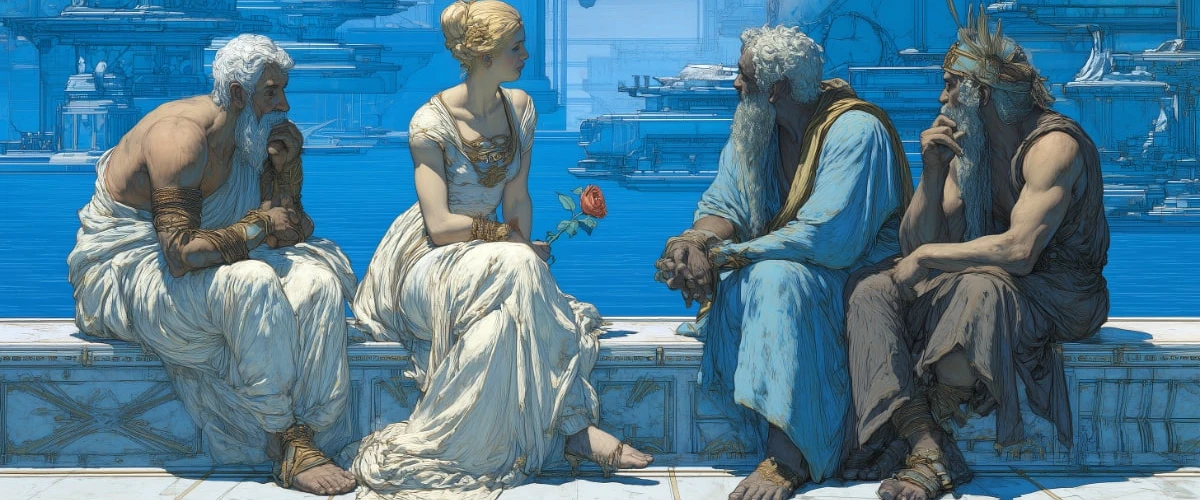

But rather than delivering a purely abstract treatise, Hart experiments with a literary form: he stages a dialogue between four mythological figures—Eros, Psyche, Hermes, and Hephaestus—to explore, confront, and critique opposing worldviews.

Each character represents a position:

• Eros: the intuition of desire as a cosmic force, the source of unity.

• Psyche: the sensitive, contemplative soul, grounded in inner experience.

• Hermes: the messenger, mediator, ironic spirit, endlessly curious.

• Hephaestus: the materialist skeptic, technician of reality, devoted to fact.

This structure allows Hart not only to express his ideas but to test their limits and critiques by placing them in contrasting voices. There’s a kind of intellectual courage here, as Hart places some of the strongest objections to his views—and to religious mysticism more broadly—into the mouth of Hephaestus.

The Disenchanted World

Hart begins with a critique of the modern world as it has developed since the 17th century. With the rise of science and rationalist thinking, nature has been reduced to a soulless mechanism, a mere object of analysis and control. The sky has emptied of its angels, the trees of their dryads, the stars of their mystery. This “modernity” has severed the mind from the body.

In contrast, Hart reminds us that before this rupture, ancient traditions saw the world as a living, meaningful reality, inhabited by the divine. It wasn’t a “magical” world in the naïve sense, but a participatory one, where every visible thing was rooted in an invisible depth.

Much of the book is devoted to a patient demolition of the various forms of materialism, mostly voiced through Hephaestus. By “materialism,” we usually mean the idea that all reality—including thoughts and rocks alike—can be explained physically or scientifically.

According to Hart:

Materialism cannot explain how the mind could emerge from the non-mental (brute matter). Hart finds it implausible that a phenomenon like consciousness could arise from something “inert”—no matter how complex—like the brain.

Materialism leads to an infinite regress, where each level of explanation rests on another that cannot justify itself. It’s the classic “turtles all the way down” problem. If one level explains the next, then we can always posit another beneath it, ad infinitum.

Materialism relies on concepts—truth, rationality, natural law, order—that it cannot ground on its own terms. In other words, consciousness cannot self-generate; truth and law presume underlying values (and again—turtles!).

Materialism assumes an intelligible universe but cannot explain why it is intelligible. One may break consciousness down into neural mechanisms, but the reverse—reconstructing consciousness from those parts—is not logically possible.

By contrast, Hart proposes that consciousness, mind, and thought are primary, and that the material world is their emanation or expression. This model, he argues, is more coherent and fertile. It is found in the works of Plato, Plotinus, Christian mystics, and Vedantic philosophers.

The World as Theophany

Hart is not simply defending a metaphysical idea, but an entire way of seeing the world. He claims that beauty, harmony, and intelligibility are signs of the divine presence. The world is not a neutral object—it is a theophany, an appearance of divinity.

He draws on concrete, often simple experiences. For example, he recounts the story of an elephant herd returning to mourn the death of their human protector. This moving image suggests awareness, memory, and ritual in non-human animals. For Hart, such scenes should awaken us to the mental depth of life itself.

His view closely aligns with panpsychism or idealism, in the spirit of Bernardo Kastrup.

Poetry, Myth, and Mystery

The book is also a plea for a poetic, symbolic, and participatory mode of knowledge. Hart resists reducing knowledge to analysis and measurement. He values poetry, art, and myth—not as escapes from reason, but as expanded forms of intelligence, capable of expressing the world’s sensual and spiritual richness.

In this perspective, language itself becomes sacred, a bearer of deep meaning. Hart writes in a baroque, elaborate, and often florid style—something that may put off some readers, but which aligns with his vision of a dense, overflowing, divine-charged world.

A Major Weakness: Evil Barely Addressed

In my view—offered humbly and within the limits of my understanding—the book’s most glaring omission is the absence of any serious reflection on Evil. Hephaestus acknowledges that human history is marked by brutality, cunning, and domination, but this lucidity is never developed theologically.

The book does not explore the mechanism of the Fall, nor how evil fits into a supposedly divine world. This omission weakens the overall project: if the world is “full of gods,” how do we account for horror, injustice, and suffering? The lack of a theology of the tragic leaves the vision incomplete.

That said, Hart does not seem unaware of this gap; he raises it indirectly through his critical character, Psyche. In the final pages, Psyche—wounded yet lucid—voices a profound anxiety: the modern world is drifting away from depth, meaning, and the sacred. She fears that our culture is sliding toward total nihilism, where nothing will have value, truth, or beauty.

This moment reads like Hart’s personal cri de cœur, a plea not to let our capacity for wonder and spiritual presence die out. Here, Hart echoes Iain McGilchrist’s thesis in The Master and His Emissary.

A Demanding and Vibrant Book — but a Bit Sleep-Inducing

All Things Are Full of Gods is a challenging book. It lays out a radical critique of modern thought, proposes a luminous metaphysical alternative, and calls for a transformation of perception. It won’t convince everyone (and Hephaestus himself remains unconvinced!). Still, it represents a philosophical act of depth—both intellectual and spiritual—where every page carries the trace of an inner struggle: that of a man who refuses to believe the world is mute.

To my mind, Hart’s literary style is another weakness. His ornate and allusive prose can weigh down the ideas, especially when paired with dense philosophy and mythological dialogues. I believe the work would have benefited from using modern characters (a scientist, an artist, a mystic, a skeptic), placed perhaps in an urban setting, which could have made the ideas more directly relatable while preserving their richness.

He also would’ve done well to keep it shorter. Some monologues—especially those of Psyche and Hermes—are too long, often soporific, and float a bit too high in the clouds. Not all characters carry the same weight either; the dialogue is essentially between Psyche and Hephaestus.

In short: an abstruse style, verging on self-congratulatory cerebral display—as if the author gets lost in the very labyrinths of consciousness he seeks to illuminate—with the precise, calculated tools of a metaphysical machine.