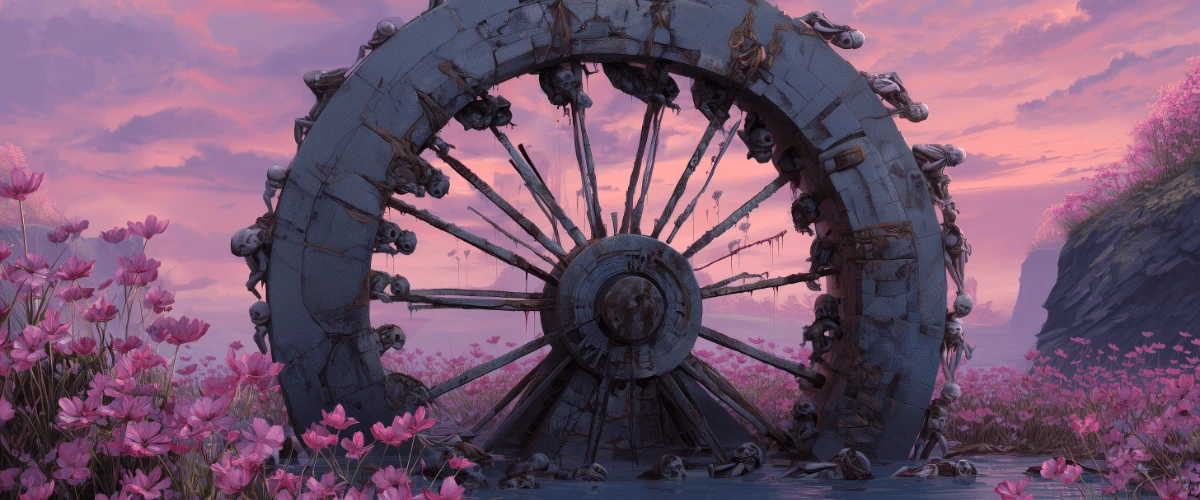

The weel

I have begun reading the Upanishads. These are a collection of philosophical texts composed in India between approximately 800 BCE and 200 BCE, forming the spiritual heart of the Vedas, the sacred scriptures of Hinduism. Unlike the ritualistic portions of the Vedas, the Upanishads focus on inner knowledge, the nature of reality, and the unity between the individual soul (ātman) and the universal principle (Brahman). They explore profound themes such as consciousness, death, reincarnation, karma, and liberation (moksha), often through dialogues between masters and disciples. Their tone is introspective and speculative, marking a shift toward a more personal and metaphysical spirituality in Indian thought.

Before these texts, Vedic religion emphasized complex rituals, sacrifices (yajña) to the gods, and the maintenance of a cosmic order through the intermediation of priests (brahmins). The connection with the divine was enacted through codified gestures, often collective, aimed at securing prosperity, rain, victory, or offspring.

The Upanishads, by contrast, question the value of these rituals by asking: Who am I, truly? They assert that self-knowledge leads to liberation, that Brahman (the ultimate reality) is found within oneself (ātman). That ultimate truth can only be attained through intuition, meditation, contemplation—in short, through an inward journey. In this, they represent a spiritual revolution: instead of seeking truth externally, in prescribed actions, they invite each individual to turn their gaze inward.

The Upanishads are not the work of a single author, but the expression of a profound current of thought rooted in a millennia-old oral tradition, emerging within and at the edges of the Vedic world. Those who wrote or transmitted them were not concerned with asserting their own identities, but with realizing the Self. Their silence about themselves may be coherent with their core message: the true Self has no name, no form, no story.

When we examine our so-called modern world, we might ask what we have learned over time—what we have truly gained from this ancient quest. These texts have deeply inspired many philosophers and physicists, and the Upanishads are never far from the hearts of those who seek to pierce the thin veil of incomprehension.

The quest—or the struggle—continues. On one hand, we have amassed staggering knowledge: the secrets of atoms, brains, the cosmos, genes, and societies. We have sent probes beyond the solar system, mapped DNA, built allegedly artificial intelligences, and interconnected billions of minds. We also know that the universe is incalculable, and that we will likely never reach the edge of what has no boundary.

On the other hand, the fundamental questions of existence remain unchanged: Who am I? Why is there something rather than nothing? What is the good, the true, the real? The wheel of fate still seems just as inexorable, our end just as brutal, ever-thirsting.

This paradox strikes hard: the more we understand how the world works, the less we seem to know how to dwell within it. Technological progress has often outpaced wisdom. Consciousness may have grown more complex, but has it deepened?

The Upanishads have already spoken of a deceptive world, a restless mind, and the confusion between appearance and reality. And here we still are. Except now it is on a global scale: distraction has become structural, the flight from Self a social norm, consumption a spiritual substitute. Modern humanity has gained the world, but risks—as Jesus once said—losing its soul.

It can be said without hesitation that there has always been—and still is—a gap, even a silent or open tension, between those who follow the Upanishadic inner path and those who live according to the social, ritualistic, or materialistic norms of their time.

The sages of the Upanishads—the rishis—were marginal figures, even within their own Vedic culture. The dominant ritual world of the time was structured around castes, sacrifices, strict social duties (dharma), and codes of purity. The cosmic order (ṛta) had to be upheld through correct action, following complex rituals dictated by priests. It was a religion of order, hierarchy, and magical efficacy—almost a proto-technocracy of the spirit: everything was orchestrated according to strict protocols meant to yield measurable effects (rain, prosperity, protection). Efficiency was the heart of the system: if the rite is performed correctly, the universe responds. It was a logic of symbolic causality, an almost contractual relationship between human and cosmos.

Modern science, in its dominant form, operates on a similar logic, albeit stripped of religious symbolism. It relies on observation, reproducibility, regularity, and control through method. It seeks to identify causes to predict effects, thereby reducing uncertainty through precision. Like the Vedic priests, today’s engineers and scientists operate in a world of rules, protocols, deliverables, and formal language.

And just as in the Vedic age, this world of technical mastery ultimately generates its rigidity, its priesthood, its orthodoxies, and its exclusions: what cannot be objectified becomes suspect; what cannot be measured is dismissed; what is not useful is marginalized. Poetry fades, and we seem eternally bound to the crushing wheels of certainties and fate.

As in ancient India, we live in an era where the power of the system conceals the depth of the mystery. Shut up and calculate is a bitter joke—and at the same time, a commandment—often thrown by physicists at their students.

And as before, we need marginal voices—contemplative, even solitary—to remind us that reality cannot be fully grasped by equations, that around the wheels of torment, in the very blood of our pain, grow the flowers, the beauty, the wisdom of an ignorant adventure: that of our awakening, the jewel of life.

But the blood remains, and incomprehension hardens around our fragile bones.